The Games We Play

For those of you who prefer a PDF version of this document, it can be found here.

Introduction

In April 2019 I conducted a survey of board gamers to find out who played hobby games, what types of games people played, and how people played games together. The results of the survey were overwhelming; I thought I’d get about 200 people to take the survey, but over 900 ended up filling it out! I’m incredibly grateful to everyone that took the time to answer my questions and provide such a wealth of information. In this short post, I thought I’d share some of the preliminary results of the survey that so many of you filled out. This isn’t going to be a full analysis of the data—with so many different responses and answers, it’s going to take me awhile to make sense of it all. The end result of this research will eventually be published in a book I’m working on, Board Games in the Digital Age, due out in late 2020/early 2021 from Bloomsbury Press. The book will present different ways of studying board games and interrogate the popularity of board games today. The data from this survey will become part of the section of the book that looks at board gamers and board game communities from an ethnographic point of view. (If you’re interested in being notified when the book comes out, you can leave your email address here.)

Methodology

In order to collect the data, I mainly used targeted social media posts and word-of-mouth to spread the survey. I also posted up flyers for the survey in my local board game stores and cafes. (I’m lucky to live in Chicago, which has a thriving board game culture, with multiple outlets for playing board games.) I wanted to survey people who already identified as board gamers, so I didn’t try to reach out to the full population. I also wasn’t as interested in exploring role-playing games or collectible card games (not that they aren’t fascinating in their own right! It just wasn’t the purpose of this survey) so I aimed my research at hobyy board gamers specifically. I sent out some preliminary tweets and Facebook posts which gained some minor traction. In the initial push, I received about 200 responses. Towards the end of my data collection period, I sent out another round of tweets, this time tagging some online board game content creators and asking them to retweet it. In one week I received an additional 700 responses. The lesson here is to reach out to people with connections to the community!

The survey itself had both quantitative and qualitative information—that is, I wanted to collect statistical data and I also wanted people to write in answers, giving me more varied responses. There are advantages and disadvantages to this sort of data collection—the survey was longer than most people wanted to fill out and people tend not to like to answer too many open-ended questions. If you filled out the survey, you probably got a bit unhappy when you saw more text boxes than radio buttons to click. But I have found that only looking at quantitative or only looking at qualitative data doesn’t give the full story; it’s better to have both. In this summary, I’m mainly presenting the quantitative data and offering some cursory looks at what it means; the full chapters in the book will go more in depth understanding how we can apply this in our board gaming lives. About 1,100 people opened the survey, but of those 1,100 people, only about 850 actually filled out the survey. This is not unusual – and there’s often attrition on the questions, so not all of those 850 answered every question.

Oh, and the signs I put up in the stores? I received one filled out survey from them. So thank you, whoever filled out the survey from the store!

Pretty Graphs

Demographic Questions

Although these questions usually come last in a survey (and did in this one), I think it’s useful to know up front the demographics of the people answering the survey questions. In my book, I’ll be digging a bit more into how different demographics answered different questions, but here I’ll simply focus on the numbers of people answering questions.

The data demonstrate that most of the people who took the survey were white (Caucasian) men, aged 25-44, from the US and the UK. This is not to say that there wasn’t great variance between the many people who contributed, or that there isn’t diversity within the board game community as a whole, but the results of this particular survey were very heavily skewed towards that identity. There are many possible reasons for this: the most obvious is that the community could be mostly white and male, but there are other explanation as well. For instance the demographics of respondents that I had for this survey could also be influenced by the way I went about getting my sample – I didn’t attempt to reach out to different board game groups online or target specific demographics with my work. Limiting my collection to just social media meant I didn’t reach people who weren’t on social media. And the length of the survey might have been a turnoff for people without as much free time. Future survey research should deliberately reach out to underrepresented groups in order to have more representation. Not including these perspectives is a detriment to the data and misrepresents the hobby.

Here’s the data broken down more specifically. The majority of people answering this question on the survey (745) were aged between 25 and 54, with 34 people aged 18-24 and 36 people aged 55 and older. Due to the nature of survey (ethics), I couldn’t officially reach out to people under 18 years of age, although obviously younger people are playing board games as well.

Because of the time/cost associated with playing board games, it’s not surprising to me that the most popular category was 35–44; this is an age when one has (perhaps) settled into a career and family, and may have some extra time/money to spend on gaming. (Obviously, that’s not true for everyone!). Additionally, this age bracket has grown up with and witnessed the rise of digital technology, which may make them more keen to spend time engaging in face-to-face social activities instead of looking at more screens.

I also asked people which gender they identified with, and the vast majority of people—563 out of 814—answered “male,” 222 people answered “female” with 18 people marking “non-binary,” 4 answering “queer,” and 7 answering “other” (more on the issue of gender-related questions below the graph).

Asking gender-related questions can be difficult because people interpret “gender” in different ways. As some people pointed out when answering “other,” gender is a construct of culture (masculine/feminine) rather than biological sex (male/female). This is true, and surveys would do well to ask multiple questions to get a full range of identities (gender identity, sex, sexuality, presenting gender, etc.). However, the vast majority of surveys that people are used to taking still use this outdated language. In fact, the software used to make this survey (Qualtrics, in case anyone is interested) defaults gender answers to just male/female….ignoring any non-binary people entirely. In retrospect, I wish I had included a button for “transgender,” as two of the “others” responded with that.

In addition, I asked people what their race/ethnicity is. This is another tricky question for people to answer because there are many different ways of identifying. I opted to use what, in the US, is the standard “race/ethnicity” survey question, to which I added an “other” category and asked people to fill in the answer if they wanted to. (I’ll discuss what I learned about this after the graph). The vast majority of people who filled out the survey were white—722 people out of 811, or almost 90%. 10 people identified as Black or African American, 2 as Native American; 31 as Asian; 2 as Pacific Islander, and 44 as other. (Because of the huge disparity in white participants vs. people of color, any sort of data analysis will be heavily skewed and unreliable, and so I do not undertake in this analysis.)

My own identity as a white researcher from the US blinded me to the way people identity differently across the world, however, and led me to default to these race/ethnicity categories. In truth I should have been more open-minded to the global experience of gaming today. For example, I didn’t realize that in New Zealand the term “Pakeha” refers to non-native people of European descent. I also should have reflected on changing demographics and included categories for mixed race/biracial identities. Here are the ways people filled in “Other”:

- Latinx/Hispanic (15)

- Mixed/Biracial (10)

- Human (4)

- Jewish (2)

- Malay (2)

- Pakeha (2)

- Slavic (1)

- Mediterranean/Spanish (1)

- Filipino (1)

- Indian (1)

- Irish/British (1)

One person noted that this should have been multiple-choice (it was) but it raises a good question about self-reporting. To have participants write in the answers to all race/ethnicity questions or all gender questions does offer the opportunity for more specific answers and user-generated responses. (I also want to interrogate the “human” answer, which I found fascinating: is that a comment about being racially blind? Is it a comment about finding race/ethnicity questions too abstract or too specific? Is it a coded way of saying that they don’t want to answer race/ethnicity questions, or that they think race/ethnicity shouldn’t be a part of survey research? Or perhaps it’s a taking a more metaphorical view that we are all of the same race?). Letting everyone write in their own answer would have opened up a space for greater diversity of content. For this purposes of this survey, I needed the information to be more quantitative, which is why I opted to use multiple choice. In the future, this would be helpful to dig down into the specific for individual answers.

Finally, I asked the open ended question, “What is your country of residence?” The vast majority of people (531 out of 802) said they were from the United States of America (one person put “America” which I included in that list). The second most common country of residence was the UK, with 94 people stating it; although I should note that in that number I did not include England (15 people), Scotland (1 person) or Wales (1 person). Additionally, one person put UK/US. The countries included in the sample were:

Table 1. Countries represented in survey

*for the sake of completeness, I included these answers here, although I am aware they are not countries. I assume the authors either misread the question or are making political statements.

Finally, I wanted to make sure that the people filling out my survey were actually board gamers. 860 people identified as “definitely” or “probably” a board gamer, with only 14 people saying “probably” or “definitely” not. This was good for my survey, as it meant that most people that were filling it out fit the parameters of the group that I was hoping to reach.

Board Gaming Questions

In this section, I’ll offer some of my findings about the way people relate to playing, teaching, and learning board games. In sum, I found that the roots of board gaming go deep, as most people have been playing board games as a hobby for over 10 years. I also found that overwhelmingly, participants play once or more a week with the same group of people but enjoy playing with—and teaching the game to—new people. Additionally, participants tended to have mixed feelings about using digital apps in games, but enjoyed strategic, cooperative, and deck building games the most. Participants enjoyed a great variety of mechanics, with worker placement the most popular, although this varies with age and gender.

Going into this survey, I assumed that a lot of people in the hobby had only recently gotten started. The past ten years have seen an explosion in the world of board games, with more games being produced and marketed than ever before. Yet, almost half of people who responded to the survey played board games longer than I had thought – 435 people said they played games for 10 or more years, and 454 people have played for fewer than 10 years. Digging into the numbers a bit more, it becomes obvious (and probably goes without saying) that the older a participant was, the longer they had played games. The most common response for players aged 35 and older was that they have played for longer than 15 years. The average length of time that someone 18-24 had played was 3-6 years, and the data correlates the older players get. While there was some variance within the answers (most age groups had a standard deviation of 1.3, meaning answers generally were within a few years of the average), it seems safe to say that, at least for the people taking this survey, board games are not a new hobby. However, almost 10% of the respondents have played for fewer than 3 years, which speaks, I think, to that increasing popularity in board gaming. Additionally, while I didn’t specifically ask this, the data would seem to suggest that most people start playing board games as a hobby in their late teens/early 20s (there were 6 people over the age of 65 who took the survey, so it’s hard to generalize from that small a sample, although 5 of those 6 have been playing longer than 15 years).

Again, almost half of the respondents (418) said that they played games between once a week and a few times a month; and I wasn’t surprised to learn that almost 40% of people who self-identity as board gamers play board games more than once a week (that makes sense!).

I was also interested to learn what game “got” people into board gaming. 837 people answered the question, listing a total of 218 games (although many people listed more than one game, and some people listed “can’t remember” or “don’t know). By a huge margin, the game that most people listed was Settlers of Catan (or, as it is now known, Catan), with 132 people naming it as their gateway game. At the same time, 139 games were listed just once, meaning that there were just about as many people who got started with more obscure/less popular games as started with Catan. The games in the “top ten” were:

· Settlers of Catan, 132 people listing it

· Ticket to Ride, 42

· Monopoly, 39

· Carcassone, 35

· Pandemic, 35

· Risk, 31

· Dominion, 19

· Betrayal at House on the Hill, 18

· Dungeons and Dragons, 18

· Magic the Gathering, 18

I was surprised to see some very new games listed—Pandemic Legacy was someone’s first dip into board gaming—and some classic games (Careers). 9 people noted that Wil Wheaton’s online series Tabletop got them into gaming rather than any particular board game.

Social Activities

One of the things I was most interested in discovering about board game players is how committed to social activities they were. In my research for the book (which has involved interviewing 40 people associated with the board game industry or online content creation), almost everyone I’ve talked to has mentioned that board games serve an important social function in the age of digital technology. That is, the argument seems to be that as we have become more and more physically separated from people (because of our phones/computers), board game playing has increased because it gives everyone a good excuse to get together for an in-person social event that forces social interaction.

I asked the survey respondents whether they tended to play with the same people or different people. My intention for this question was to find out whether people had a steady game group or whether they attended events in order to meet people. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the majority of people (603/856) played with the same group. Only 2% of respondents said they mostly played with new people.

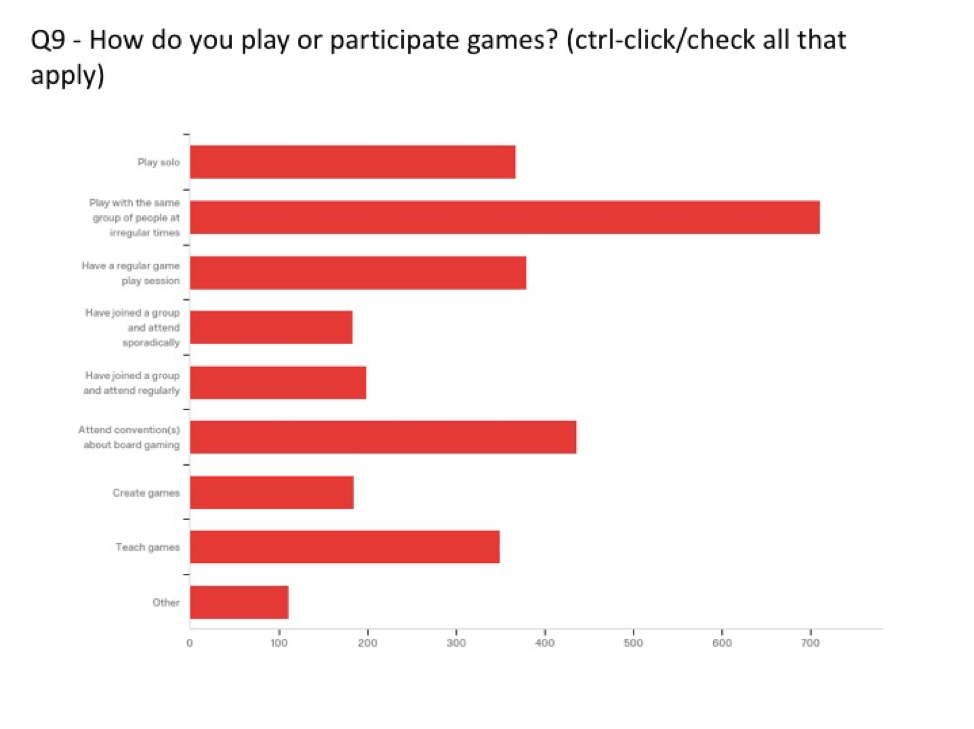

But beyond just playing games with people, I wanted to dig down more, to find out how people played socially. I asked participants to how they participated with board games and let them click as many ways as they wanted: the answers thus reflect the variety in the hobby.

Digging into this data a little bit, we can see that there is a great variety of ways that people participate in games—it’s not just playing. As a hobby, board gaming is creative (185 people said they have created games) and social (almost everyone wrote that they play games with people or attend conventions).

- 81.72% play with the same group of people at irregular times (711 total)

- 50.11% Attend conventions about gaming (436 total)

- 43.68% have a regular play session (380 total)

- 42.18% play games solo (367 total)

- 40.11% Teach games (349 total)

- 22.87% Have joined a gaming group and attend regularly (199 total)

- 21.26% Create board games (185 total)

- 21.15% Have joined a gaming group and attend sporadically (184 total)

870 people answered this question with a total number of responses at 2,922. This means that the average number of ways an individual participates with games is 3.4 (although in the data, 183 responses listed only one way that the individual participated. By far, the most common single response was “Play with the same group of people at irregular times.”)

Please note that this question wasn’t asking what people preferred, but rather what people actually did. There are a variety of reasons that might affect how people answered, including where they live (if they are not close to many other people, that would affect whether they played regularly or sporadically) or financial situation (in terms of affording travel for and attendance at board game conventions).

The “Other” category on this question was filled with a great variety of information, with over 110 people giving various answers, including playing board games online, play testing, moderating board game play, and (most commonly of all), playing with just a spouse.

Analyzing this data a bit more, some interesting comparisons in terms of gender and age can be seen. While many of the categories are pretty consistent in terms of gender, some are more varied. For instance, a greater percentage of men play games solo than women (46% to 32%) while a greater percentage of women play games with the same group at irregular times (85% to 80%). People that reported being non-binary/queer/other play solo even less frequently (23% said they do) but in groups even more so (91%). A greater percentage of men report attending conventions (54% to 45% non-binary/queer/other to 41% women). Interestingly, a greater percentage of non-binary/queer/other people report creating games (27%) compared with men (24%) and women (16%). Men tend to have a regular group of people they game with (47% report this) compared with women (32%) and non-binary/queer/other people (41%). This gender breakdown seems to indicate that women and non-binary/queer/other people tend to be more social with games, but men tend to play with the same group of people more often and to be more public with their gaming.

In terms of age, some fascinating correlations can be seen. For example, the older someone is, the more likely they are to play games solo, and the less likely they are to play games with the same group of people at irregular times. 18-24 year olds are less likely than any other group to play with a regular group of people, which makes sense given that younger players are probably more likely to be mobile and exploring different communities. These younger players are also the least likely to go to conventions (only 32%), while the most likely to attend conventions are the 45-54 year old age group, with 56% attending. This likely has to do with the cost of the convention coupled with the ability to readily travel. The oldest demographic in my survey (55-74) are also the most likely to create games, with 31% reporting that they do; interestingly, the next highest age group to create games was 18-24 year olds, at 26%.

I was also curious to dig deeper on how games are introduced to new groups of people. I asked whether, when playing a game that you’ve already played, if the respondent enjoyed playing the game with people who were unfamiliar with the game. The overwhelming response, with 534 people (62.5%) was that they liked it either somewhat or a great deal. Only 33 people (3.9%) didn’t enjoy playing a familiar game with those that haven’t played before.

And along those same lines, I was curious to know how much teaching a board game might influence people’s ideas about playing games with new people. 635 people on the survey (or, almost 75% of the respondents) said that they liked teaching games to other people; this is more than even liked playing the game with new people! It seems that generally, we like to teach games to new people a little more than we like to just play a game with new people. However, a greater number of people also disliked teaching games: 75 people total, or 8.8% of the sample, did not like teaching games. The difference between this question and the last is that fewer people felt neither like or dislike about teaching; teaching games is more polarizing.

Types of Games

The last group of questions I asked focused on the types of games people liked to play, as well as the elements of games that people most enjoyed. I wanted to interrogate the stereotypical notion that that board games are a palliative against the digitization of contemporary life, so I thought it would be worthwhile to find out whether people like to play games with digital apps. Quite a few games have been released recently that use apps or websites as central to the game play. The results were perhaps the most evenly distributed of any question I asked on the survey, with 364 people liking the use of apps, 201 people disliking the use of apps, and 240 people neither liking nor disliking.

A great many people offered rationales for why they did or did not like games with digital apps; while I haven’t fully dug down into this data yet, some preliminary ideas are that, on the one hand, apps can “add to the atmosphere and also tend to let there be no narrator role so everyone can play.” They can also streamline aspects of game play that some players may find tedious, like keeping track of scores or randomizing enemy play. They also make the game experience “varied” and “easy to change.” On the other hand, some players “don’t like to look at my phone while I’m playing” while others think it feels “awkward and like lazy design.” They can also “take away from the social interaction.” Digital apps can be seen to be disruptive to the game play, and players commented on the lack of immersion they create. Some of the most passionate comments mentioned that people play board games specifically to “get away from the digital.” Most of the middle of the road comments noted that it “really depends on the digital app and how it is integrated with the game.” Many contributors mentioned specific games: One Night Ultimate Werewolf was generally seen to use the app in a really positive way, as does Mansions of Madness and Alchemists. Few people named any games that didn’t use the app well. Many people also noted that they do not like to play app versions of board games, although this is somewhat complicated by the fact some people said that they do like to play app-versions of board games in a previous question (“how do you play/participate with games”). Further exploration of this topic will, I’m sure, reveal greater variety in the use of apps and the digital in terms of board game play.

The last couple of questions dealt more generally with types of games and mechanics that people preferred, and reveal a wide range of opinions. Respondents were given the option to check as many different answers as were applicable, so the data pool is enormous for all of these questions.

Question 21 asked respondents which style of game they preferred. 835 people answered the question, with a total of 3,685 responses. Only 84 people (about 10%) chose only one style of game, with Eurogame the most popular single choice by far (e.g., people who only prefer Eurogames). In general, Eurogames (644, 77%) and Cooperative games (589, 70.5%) were the two most popular styles of games, and wargames (178, 21%) and collectible card games (184, 22%) were the least popular. (I’m not surprised by this as I specifically reached out to board gamers rather than War or CCG gamers.)

Furthermore:

- 58% prefer Deck building games (486 total)

- 48% prefer party games (401 total)

- 45% prefer role-playing games (373 total)

- 44% prefer Ameri-game/Ameri-trash (369 total)

- 43% prefer abstract game (360 total)

- 12% marked “Other” (101)

It’s hard to make any sort of generalization about why different types of games might be preferred over other types of games. It could be that the popularity of particular games has affected the results, or the longevity of games in the market may make a difference. Some of the most popular board games over the past two decades have been Eurogames, and some players may find that they enjoy what’s hot at the moment. At the same time, as researcher Dinesh Vatvani found, players rate complex games like Eurogames more highly simply because they are more complex; there may be a bias towards complexity. Perhaps players rate more complex Eurogames higher because they are more challenging and take more effort to play—games that require little effort seem less valuable and reflect more positively on the player themself. Of course, it is important to keep in mind that 90% of the participants chose multiple game styles, so very few people are wedded to just one style of game.

Some of the “other” types of games included Legacy games, dexterity games, casual games, “artsy” games, and deduction games. One of the things this question and the next question revealed is the overlap in the way people talk about or describe games. Is a “cooperative” game a mechanic or a style? (I included it in both questions.) How is an abstract game different from a Eurogame? What this revealed to me is that the way board gamers describe games can often be specific to the gamer; the overlap between “style” and “mechanic” is clearly present, as some said mechanics and styles were the same thing, and some saw them as quite different.

In fact, when I asked the respondents what mechanism/mechanic did they prefer, answers were again all over the place. This time, I received 5010 responses to the question, with 834 answering in total. Worker Placement (639 responses, 77%) and Cooperation (538, 65%) were the most popular mechanics, while Trick taking (which I typo’d as trick tacking…oops!) was the least popular with 181 people (22%) clicking it. Interestingly, in a 2018 analysis of data scraped from BoardGameGeek, Dinesh Vatvani found that fewer than 1% of the games on BGG included “worker placement” as a mechanic, so it appears as though this could be a growth area for board games.

Obviously, however, there is great variance in the mechanics that people enjoy playing, and almost every participant clicked more than one. In total, here are the mechanics that people prefer:

· Worker placement, 77%, 639 total

· Cooperation, 64%, 538 total

· Deck building, 61%, 512 total

· Card/Die drafting, 54%, 454 total

· Area control, 51%, 424 total

· Puzzle, 46%, 388 total

· Legacy, 38%, 317 total

· Press your luck, 37%, 307 total

· Secret identity/Social deduction, 36%, 297 total

· Combat die rolling, 28%, 232 total

· Roll/Flip and write, 27%, 228 total

· Auctions, 26%, 216 total

· Roll and move, 23%, 190 total

· Trick taking, 22%, 181 total

· Other, 10%, 87 total

The “Other” mechanics that people enjoyed included asymmetric powers, engine building, hand management, and storytelling, although there was a great variety revealed in the 87 answers. (Indeed, a few people answered that it didn’t matter because they just enjoyed the social connection with others.)

Breaking down this data via age and gender again, we can see some fascinating results that reflect differences in preferred mechanics. While many of the categories were relatively evenly preferred, male players hugely preferred Worker Placement (81% listed it) compared to female players (64%) (non-binary/queer/other players were closer to the male percentage, at 79%); the same disparity is seen in Area Control games (Men and non-binary/queer/other players with 56% and 59%, respectively, and women with 36%). However, women greatly preferred puzzle games (59%) compared to men (41%) and non-binary/queer/other players (48%). Women and non-binary/queer/other players also greatly preferred roll and move games (36% and 34%) when compared with male players (17%), but male and non-binary/queer/other players preferred auctions (31% and 28%) more so than did women players (13%). Just looking at these statistics, it seems as though men seem to favor games with more direct competition and strategy, while women seemed to favor games with more individual achievement (although, of course, players of all genders liked every type of game, so these are just generalizations).

Age didn’t seem to make as much of a difference as gender did in terms of mechanics preferences; there were only a few types of mechanics that had significant differences. Most tellingly, the 18-24 demographic heavily preferred Secret Identity games (with 53% reporting it as a favorite) while no other age group liked it nearly as much (25-34 year olds were the next highest, with 38% preference). This correlates with the social aspect of gaming; secret identity games are generally much more social and interactive than the other types. The older age group of 55-74 more heavily preferred area control games (61%) compared to everyone else (the next highest preference was 45-54 at 54%). Worker Placement, again, had some variance, with younger players preferring it less (65%) compared to the 35-44 demographic (82%).

Finally, I asked two rather complex questions, and while I’m still sorting through what this all means, I think the answers are revealing in the diversity of the board game community. Specifically, I asked players how well they learned a game depending on the method: reading the rules by yourself, reading the rules with others, watching gameplay videos, being taught by someone, figuring it out with others, or “other.” The graph below shows just how complex this answer became:

On the one hand, most people seemed to learn the rules best by being taught by someone who knows how to play, although more people than I had assumed simply read the rules on their own. Every age group seems to follow this spread. Similarly, I expected to find that a lot of people watched online videos to help learn rules, but I didn’t expect that fewer people could figure it out with others than in other ways. Some of the other ways that people learn to play is through playing the game through once by oneself or watching other people play the game. Importantly, very few people even marked the category of “not very well at all” in terms of learning the game, meaning that most players are pretty confident in their styles of learning.

Along with the next question, I’m interested to do some statistical analysis on these questions to figure out ways that people engage in games and how that differs by what they enjoy in games (I’m not a statistical scholar, though, so I’m having to learn a whole new set of methods for this!).

And that brings me to the last question, which was the most varied of them all, and was really intended to find out what people enjoyed the most about playing games. I asked respondents to agree or disagree with various statements about their favorite parts of playing games: Table presence, the artwork, learning the rules, winning the game, completing it successfully, beating others, learning the strategy, luck, socialization, or flavor text. The following graph might be hard to see because of the range of answers, but I’ll summarize afterwards.

Here’s a preliminary look at what I found. I first assigned a value to “like,” with “strongly like” assigned a 5 and “strongly dislike” assigned a 1. I averaged each of the categories to see which were the most liked and most disliked components of board games. By far, the most liked aspects of playing board games was socialization, scoring a 4.5 out of 5, with a standard deviation of .74 and a mode of 5. (Mode represents the most common answer given while standard deviation is how close to the average most answers are – the lower a standard deviation, the closer to the average.) The next highest categories were “learning the strategy” (4.28 out of 5, mode of 5, standard deviation of .83) and “table presence” (4.2 out of 5, mode of 4, standard deviation of .82). The lowest categories—meaning the categories liked the least—were “luck” (2.5 out of 5, mode of 2, standard deviation of 1) and “beating others” (2.5 out of 5, mode of 3, standard deviation of 1.17).

Table 2. Favorite parts of games

Analyzing this data a bit more, the higher the average, the lower the standard deviation. This means that people generally agreed on what they liked, but there was more variance in what they didn’t like. For example, “beating others” scored the lowest, but had more people differing on their ranking: more people ranked this 5 than ranked the most liked (“socialization”) 1. The mode reflects a similar agreement; with the exception of “beating others” (which also had a larger standard deviation), the repeated values corresponded to the average. “Beating others” seems to be the most varied answer of them all, although still coming out with the smallest average.

Following this I averaged out what each of age group and gender considered their favorite. However, a comparison at this level revealed only minor differences in how different demographics favored different aspects of games, but nothing hugely significant—that is, each age group and gender identity tended to answer the questions similarly, and with similar modes and standard deviations.

Table 3. Demographic Data

As you can see by looking at the table, while there is some variation in all the answers, there is nothing at this level that says there are significant differences between how different ages or different gender identities answered this question. The biggest difference lay in the “Learning the Rules” category, where age and gender identity reflect minor differences. In terms of age, the 55–74 demographic averaged 3.46 while the 25–34 demographic averaged 2.87. I suspect this has to do with the fact that 25–34 year-olds may not have as much time generally to learn and play games. And men prefer learning the rules (avg: 3.14) more than women do (2.54), although again this isn’t a huge difference.

Throughout it all, perhaps nothing illustrates why people like to play games than the entwined connections that this question illustrates. “Winning” is actually relatively unimportant to many game players; but completing the game is important. We like to work with others in order to complete a task, whether or not we’re cooperating or competing. I think that says something really nice about the human condition: Playing with others is the most enjoyable aspect, but beating them is not. Game art and table presence is crucial, and flavor text is enjoyed, but relying on luck to get through the game is disliked. We like to be challenged, we appreciate the care and attention that goes into the things we like, and we like to be responsible for our own decisions. I wonder if this same survey was given to players of video games (where there is often not as much face-to-face contact and the game controls a lot more of the action), if the numbers would be skewed differently.

Final thoughts

Board gaming is obviously a massive hobby, and board gamers are an effusive group of people. There is a mountain of data left to sift through, and it only keeps growing: almost 500 people responded that they’d be interested in a follow-up to this survey, and at the end of May I sent an additional few questions to those people to further deepen the research in terms of diversity and inclusion. If nothing else, this survey has indicated that there is a great deal of interest in finding out more about this hobby and the people that are part of it. In the following weeks I’ll be parsing the qualitative data as well.

The results of this survey highlight a number of things. First, the demographics of board gamers (at least the ones who filled out this survey) are skewed heavily white and male. I am not surprised by this, having attended conventions and events and seeing the makeup of the others who attended. Greater care needs to be placed on making board gaming a more inviting space for people of color and women (as well as other less-present voices, like queer and trans people). One of the purposes of my book is to present some avenues for how we might do this, like engaging with the industry on creating more diverse representations in games, or working with local groups to reach out to marginalized people.

Second, and along with the first, gaming for most of the people who took this survey, is about socialization – and not just socialization with people that you already know. Many people use board games to meet other people, to find friends, to seek out new relationships. We like to play games with people we know, of course, but we also enjoy finding new people through the hobby. Perhaps because board gaming is a relatively non-mainstream hobby (although it is growing!), board gamers feel gregarious with others who enjoy it—like, finding someone who is into this niche thing that you’re also into bonds us. (And that being said, there’s still a sizable population of board gamers who enjoy playing solo too.)

Third, just because the demographics argue one type of identity, doesn’t mean that all board gamers are the same. There is an incredible diversity of interests and passions within the hobby. But overall, more people agree on favorites than disagree: what I mean is, just in terms of numbers, fewer people said that things in the board game field were less favored to them. Board gamers tend to think more things are fun and enjoyable and fewer things are not fun or unenjoyable.

Fourth, many of the lessons that board games teach us can be applied to other aspects of our lives. For example, the survey found that simply reading the rules of a game may help some people learn the game, but most people tend to learn interactively, either by watching videos, learning with other people, or being taught by someone. Putting this into practice, we can apply this form of learning to our classrooms or work places, where instead of handing a student a textbook, we can design strategies where learning takes place within groups. Of note, this is not a new idea: many people have been focused on using games and ludic elements in education for years. The survey supports this work.

Finally, as the board game industry continues to grow, and more and more games flood the market, there is going to be a very real problem of how to make new games different from what’s come before. While worker placement might be the most popular mechanic, game creators are always trying to come up with new ways of exploring familiar mechanisms. Players seem to want innovative new mechanics, themes, and elements; one might think that integrating digital apps may be one way to go, but many people don’t particularly like them.

At the same time, this survey also reveals a number of absences that should be filled in. As mentioned, the vast majority of people who filled out the survey reported being white and male – yet, there is a sizable population of women and People of Color in the board game hobby. Much more data needs to be collected to ensure a diversity of viewpoints from all corners of the community. What are the unique challenges of the Black gamer? Or the Queer gamer? Or the Trans gamer? My survey didn’t seem to reach many in those populations, and a more targeted approach in the future would be worthwhile.

In this report, I’ve presented the data just as is, and tried to offer only a little commentary on what it means. The purpose here is just to share the preliminary results; as I mentioned, it will be a few months before I’ve been able to sift through everything and get a sense of how to put it all together in meaningful ways. But I hope that seeing the hobby abstracted in this way, and noting the connections between what the survey shows and your own experiences, helps to frame board gaming as a more universal, more generous, and more engaging hobby. (Again, if you’re interested in being notified when the book comes out, you can leave your email address here.)

Paul Booth is a Professor of Communication at DePaul University in Chicago, IL. He is the author of a number of books about fandom and about board games, including Game Play: Paratextuality in Contemporary Board Games. He is currently working on Board Games in the Digital Age, due out in 2020 from Bloomsbury.