Extinction Rebellion? Roleplaying, Death, and Ethics

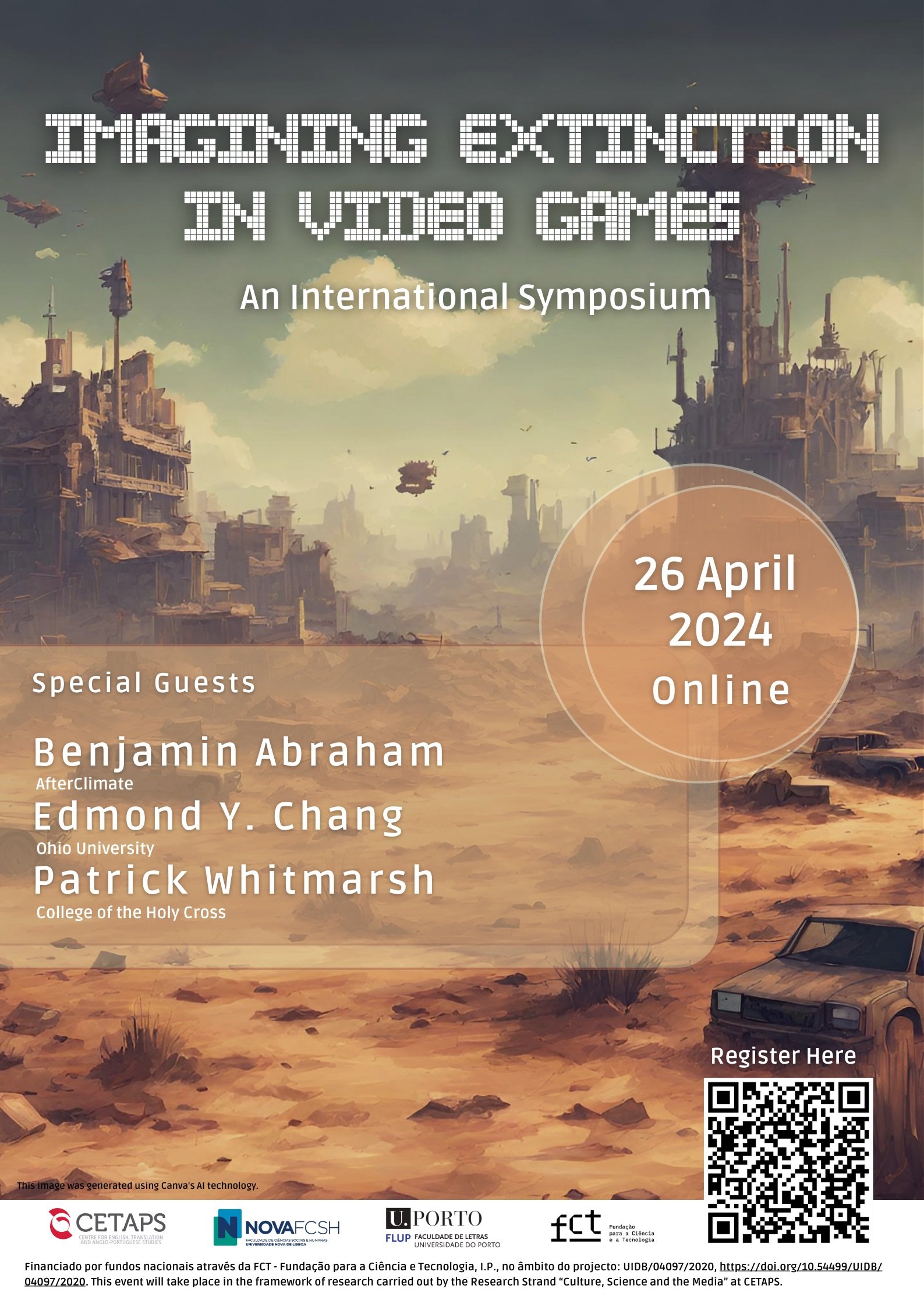

On Friday 26th April, Chloé Germaine presented her work at the Imagining Extinction in Video Games Symposium, hosted by the Centre for English, Translation, and Anglo-Portuguese Studies at Universidade do Porto, Portugal.

The symposium generated a rich scholarly discussion about the ways to approach, critically assess, and respond to the representation of ‘extinction’ in games. The keynote address by Benjamin Abraham underscored the importance of the material realities of the video game industry in these discussions, not least the ecological and habitat destruction carried out in the making and upgrading of video game hardware. You can read a digest of his fascinating talk, and find links to the research underpinning it, over on his blog.

Why (Not) Video games?

For her contribution, Chloé chose to focus on roleplaying games, specifically considering the positive contribution of tabletop (analogue) roleplaying games in the ongoing promotion of gaming as an ecological media.

This choice comes from desire to advocate for the importance of tabletop gaming in our discussions about the role of games in supporting cultural and social change on environmental issues. At a very basic level, the development, production, and consumption of tabletop games is less environmentally catastrophic than video games - a point also made in Ben’s talk. While there are aspects of the tabletop gaming industry’s production and comsumption cycle that could be hugely improved in terms of sustainability and reducing harm, it can continue to exist as an industry without being a contributor to growing carbon emissions and ecological destruction.

Chloé also points to the unique affordances of tabletop games in engaging players with the questions of ecological responsibility. The collaborative storytelling techniques and hackable mechanics of TTRPGs (tabletop roleplaying games) engage players directly in worldbuilding, inviting them to reflect on the interrelationship between humans, more-than-humans, and the environments we co-create. The virtual environments of TTRPGs are co-creations between human players, rule systems, more-than-human components, and imagined beings, composed of relationships, bonds, and agreements that must be re-negotiated at each moment of play for the world of the game to be sustained. Nick Mizer’s work on this issue points to the way such interactions create a kind of independent subjectivity that is the world of the game, a process through which players ‘cultivate and respect the concreteness of the imagined world, rather than bending it to meet other goals.’

Chloé further suggested that roleplaying games provided the original engine for the first narrative-based video games. As Aaron Trammell has discussed at length in his chapter for the volume Material Game Studies, analogue games provide the underlying ‘infrastructure’ of video games.

Extinction Rebellion

Chloé’s talk went on to problematize the idea of ‘extinction’ as it is typically applied in popular culture and environmentalism, drawing on scholars who have levelled criticisms at the idea.

Audra Mitchell argues that extinction is a manifestation of global structures of violence, specifically those of colonialism and neo-colonial capitalism. What the event of ‘extinction’ destroys are ‘resources’ held to be valuable in terms of their instrumental use for humans. Mitchell identifies this rhetoric in words such as ‘species’, ‘ecosystems’, and ‘biodiversity’. Meanwhile, the story of extinction is apocalyptic, reflecting the worldview of Euro-descendent people, rather than alternative viewpoints and cosmologies that might offer more generous and productive ways at engaging with the issue of ecological destruction.

Chloé also drew on Federico Campagna’s philosophical treatise, in which he describes the mode of reality that governs our present as ‘Technic.’ In the world of Technic, extinction is a feature, and not a bug, of the world system. According to Campagna, as the present reality-system, Technic determines the way in which all things exist. It reduces everything to its instrumental value, and erases individual beings in favour of seeing them as merely ‘positions’ in an infinite chain or series. Technic is an ontology of positions not things, in which individual life is not granted meaningful existence. Campagna argues that the concept of extinction captures the nihilism of such a reality-system.

Campagna explains the conceptual continuity between extinction and Technic by comparing ‘extinction’ relation to ‘death’. Death befalls an individual living thing, whereas extinction befalls an abstract category. The species of panda can become extinct, but this is not the same as the death of many individual pandas. In extinction, according to the logic of Technic, ‘panda’ is a position in the series we know as ‘species’ and, therefore, always potentially ripe for reactivation within a productive apparatus, whether or not any individual pandas are actually alive. Ashley Dawson’s 'radical history' of extinction points to the way extinction discourses have given rise of bio-capitalistic endeavours that reveal just this logic: the rush by tech and science corporations to claim the DNA of endangered species as intellectual property.

Bringing Campagna, Mitchell and Dawson’s critiques together, Chloé pointed to the material realities that undergird stories of extinction. Extinction is not just a fear that grips our minds but also real violence. The abstraction of categories such as species is also precisely what sanctions the extractive violence resulting in mass death. We can feel this contradiction in the way extinction is often presented to us – in statistics. Saying, the ‘earth is losing a 100 species a day’ is shocking, for sure, but it also reiterates a worldview that places humans at a distance from the earth they share with others.

The World of Mörk Borg

Designed by Pelle Nilsson and Johan Nohr, Mörk Borg is an old school revival roleplaying game set in a dying world in which players are the misfits and scum left fighting for riches they will never be able to enjoy, or for redemption that will never come. The world is not yet dead, but its demise is predicted with absolute certainty by Basilisks that lie in Bergen crypt, uttering prophecies that are translated into scripture and peddled to further the selfish ends of those who would claim power.

The grimdark setting combines with OSR vibes, creating a game that eschews predefined endings, is deliberately punishing in terms of character survival, and frustrates ‘satisfying’ story arcs for players who would set out to master the game. There is an emphasis on spontaneous rulings determined by the strange situations that occur. This is emphasized in the disruptive art-punk style of the rulebook, which leaves much of the game system to situational interpretation. Randomness and lack of player agency is encapsulated in the game’s approach to the end of the world: roll a die and see how much time you have left: d100 years of pain, perhaps? Or merely d20 months?

In a playful mimicry of religious ritual, Mörk Borg deals satirically restages millenarian and apocalyptic imaginaries of extinction. Through absurdity the game pokes fun at the Manichean underpinnings of Western cosmologies, and their shady dichotomies of good and evil. The ‘doomsaying’ that is built into the gameworld and mechanics reveals the flip side of mainstream environmentalism’s desire for a certain future.

Bad Environmentalism

The source material for Mörk Borg recalls Nicole Seymour’s concept of ‘bad environmentalism’ and helps to puncture the classist, racist and anthropocentric sanctimony often found in mainstream environmentalism.

The morally dubious cast of characters, which includes the players as well as NPCs, disrupt the logic on which ecological destruction is founded: the idea that the natural world is valuable because of its value to humans. The colonial-capitalist ground of ecological destruction, the imperial and racist appropriation of land from those deemed ‘unfit’ to manage it, both in the past and under present neo-colonial regimes of conservation and development is also satirised. Those claiming authority and ownership over the land in Mörk Borg are fatuous, grasping self-proclaimed lords and the sanctimony and self-righteousness we associate with moral authority over climate change finds a distorted mirror in a world of mocked kings and corrupt priestesses. The game also makes clear the connection between ecological decay and social injustice, describing the region of Wästland, for example, as one in which the poor have been taxed into starvation, the contents of their larders and storehouses carted off by the King’s men.

Death in Mörk Borg

Chloé’s paper notes that death is everywhere in Mörk Borg. The rulebook is full of images of wepaons, body parts, and acts of violence and players are encouraged to mete out death to the adversaries they encounter. At the same time, players are also very likely to die on the roll of a die, their weak characters vulnerable to the probabilities stacked against them. All this suggests an irreverence about death, but this belies the care and attention paid to death within the game.

Despite a thematic preoccupation with extinction and annihilation, what Mork Borg confronts players with is the intimate and subjective experience of death. For example, in Red Moon Roleplaying’s actual play of the scenario, ‘Rotblack Sludge’, one player character spends much of his time befriending decaying corpses found in a dungeon. He talks with them, shares his food, and voices his hopes and fears, at one point event picking up a corpse to show it to the other players - much to their dismay. In the written scenario, the corpses are scantly described, and, depending on dice results given in a table, might reanimate to become enemies. This doesn’t happen here. Instead, the GM describes the bodies as a family, details the items they have on their bodies and the intimate ways in which they are arranged with one another. The player takes his cue from the GM, and, rather than interacting with the bodies in order to further the plot or achieve lusory aims (such as finding items or clues), he pays attention to the bodies in other ways. These roleplay moments with and among the dead were about stopping to pause in the gameworld, to deepen the affective resonances of the encounter, and to explore death as a fate that befalls individuals, even those who are unknown and nameless. The scene provokes feelings of responsibility, awkwardness, and of ethical difficulty – all in the midst of a game that promises ‘a spiked flail to the face’. This is just one of the ways that Mörk Borg undercuts extinction narratives with an intimate exploration of death, the death of humans, more than humans, and of environments.

The continually evolving worlds of TTRPGs are an invitation to embrace uncertainty, an uncertainty that is often erased by the finality of extinction and apocalypse narratives. Roleplaying isn’t about endings, but about what Donna Haraway has called ‘staying with the trouble’ of life on a damaged planet. Mörk Borg might seem ask its players to imagine the annihilation of a world, but, really, its gameplay is all about working out how to live a life among the dying. In this way, Mörk Borg engenders an experience of ecological belonging that is, as described by Tim Morton, characterised by feelings of unreality, of a distorted reality, feelings of the uncanny and the weird. Mörk Borg creates a space, then, for the experience of ecological data, and it is one that forces players to examine their ethical relationships with ecological others, with the feelings behind the statistics of extinction, to pay attention to the dead and the dying.