Women in Historical and Archaeological Video Games

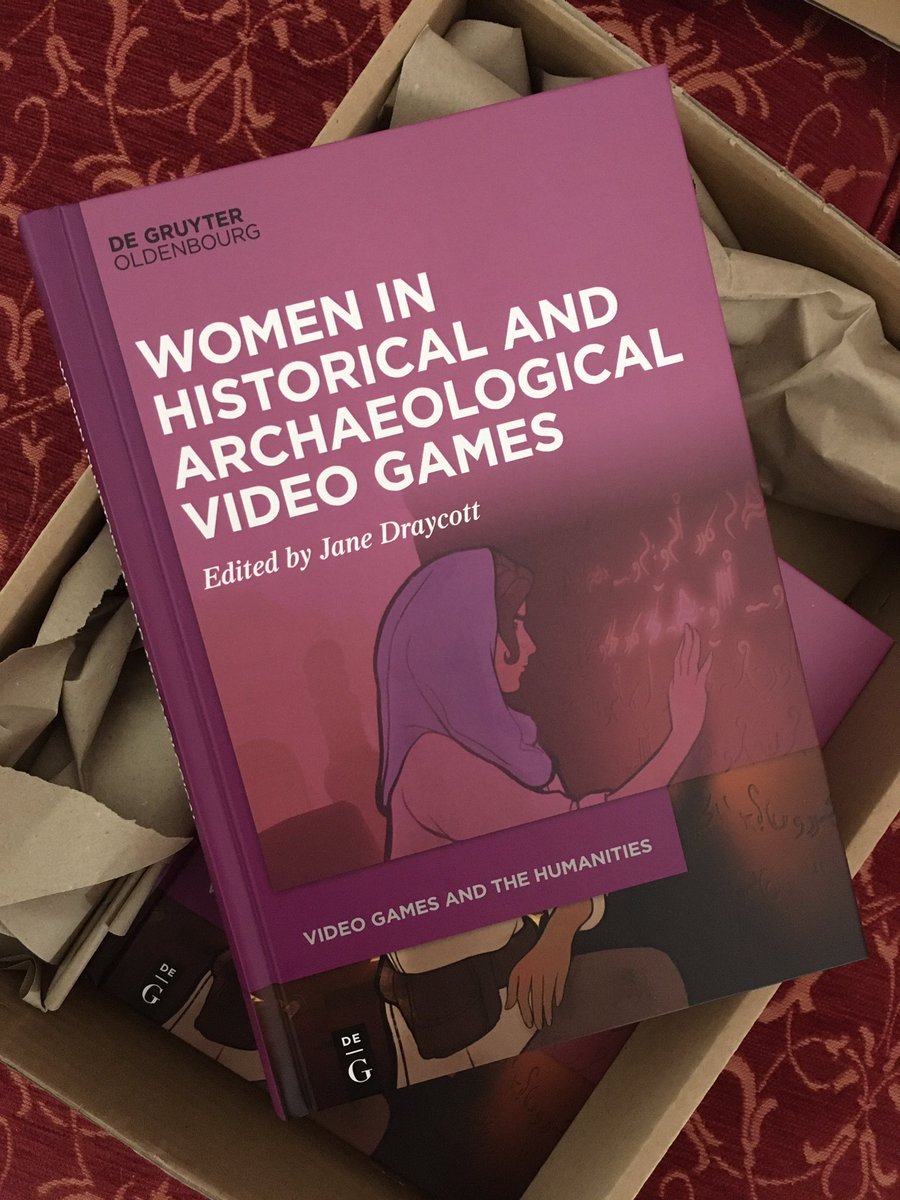

The front cover of Jane Draycott’s (ed.), Women in Historical and Archaeological Video Games. Photograph taken by Jane Draycott.

Women in Historical and Archaeological Video Games

Edited by Jane Draycott

Berlin: de Gruyter, 2022

ISBN: 9783110724196

Review by Jennifer Cromwell

Women constitute approximately half of the world’s population, and account for over 40% of gamers and over 45% of professional archaeologists,1 and yet they continue to be underrepresented in video games and relevant scholarship, both as the object of study and as authors of research. Women in Historical and Archaeological Video Games, the ninth volume in de Gruyter’s series Video Games and the Humanities, addresses this gap. Following the introduction by the volume’s editor, Jane Draycott, 13 chapters present diverse approaches to this topic, drawing upon an equally diverse range of games (see the table of contents here). Across the contributions, games are discussed that were published between 1992 and 2020, by independent developers and big budget (AAA) studios, and that focus on a wide range of time periods, regions, and cultures, including the archaeology and heritage of fictitious worlds. Indeed, on the latter point, the inclusion of the Legend of Zelda franchise expands what an archaeology game is, with Smith Nicholls demonstrating the different ways in which it can be understood as such.2 Rather than go through the volume chapter-by-chapter, I’ll instead discuss the contributions by looking at the following points: the question of historical accuracy, the opportunities presented by female characters, methodological approaches, and the issue of archaeological branding.

The question of historical accuracy in video games is a bit of a thorny issue. Scholarship has discussed in some detail the level of accuracy in games, as well as the relationship between accuracy and authenticity and what the latter contributes to game design and interpretation. But do games even have to be accurate? On one hand, certain developers stress the level of accuracy within their games, note particularly the Assassin’s Creed franchise, with a resulting fetishization of experts (Draycott; p. 14). However, in terms of women, the notion of ‘accuracy’ has been weaponised by those wanting to keep female characters out of games. As such, demonstrating historical accuracy goes beyond an analysis of game content and becomes a defence against such attacks, highlighting the agency of women in different historic periods, and notably their roles beyond the domestic context. Several papers focus on this issue: Manning for Assassin’s Creed Odyssey (Classical Greece), Meier for various Viking Age games (especially Expeditions: Viking and Dead in Vinland), and Webb for Han Dynasty women in 3rd century BCE China in Total War: Three Kingdoms. As each author demonstrates, female characters are often accused by players as transgressing male spaces (Webb; p. 112) and are perceived as being too visible in the game, even when statistically less present than male characters (Manning; p. 61). A major point that arises from each of these studies is how we have arrived at this situation, concerning the popular perception about the roles of women in antiquity (or rather, conversely, the restrictions imposed upon them). A significant contributing factor is the influence of dominant historiographies, typically produced by white western male scholars, which have focussed on the role of men, often as recorded in the words of ancient male authors. While the past few decades have witnessed a growing shift in the direction of scholarship, it takes considerable time for such work to reach a popular audience, and even more time to challenge long-ingrained understandings. In this respect, I’m particularly struck by a comment of Jose M. Galan, an Egyptologist who served as a consultant for Assassin’s Creed Origins: “we have to understand that the image we have of Ancient Egypt might be as wrong as the one portrayed in videogames. We’re not 100% sure what happened.”3 Apart from his general opinion of the type of history shown in video games, more important is the point that there is so much we do not know about history, and that what is presented is a reconstruction based on a partial and more-often-than-not biased body of evidence. The above noted papers are an important demonstration of the historical evidence for women in roles deemed ‘unhistorical’ by some players; even if the evidence doesn’t always support the precise roles portrayed in the respective games, the possibility presented by the historical lacunae allows developers to push boundaries and experiment in these gaps. Braun’s paper on Queen Nefertiti (based on her inclusion in the Assassin’s Creed Origins DLC The Curse of the Pharaohs) particularly emphasises this point. The academic debate over whether Nefertiti ruled in her own right is not crucial for the history of her reception: “The possibility alone was enough to build a wide range of narratives around her character” (p. 150). And developers should be able to play in these spaces, without the fear of being held to a prescriptive idea of ‘accuracy’, especially when such a concept is used to gatekeep female characters from games, as well as from world history.

The inclusion of female characters is not just a possibility resulting from the historical record (or gaps in it), but one resulting from the specific affordances that female protagonists possess. In this respect, two chapters particularly standout, Beal’s analysis of Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice and O’Sullivan’s study of Detention, two very different games that respectively explore psychosis and national trauma. In Hellblade, Beal argues that the game would not have been as impactful if it had a male lead, due to the stigma that continues to surround male mental health; instead, the use of a female protagonist makes the conversation more approachable. Within this, the treatment of Senua’s psychosis and schizophrenia is also important. She is never portrayed as broken or dangerous. Rather, her personal context, not her symptoms, is the focal point, thereby validating her experience and not questioning her reality – a reality that is often difficult for players to handle (speaking from my own experience of the game), especially due to the game’s immersive use of sound. Detention is a survival horror game set in 1960s Taiwan against the background of the White Terror (the period of political repression against civilians that lasted from 1949 to the early 1990s). Unlike other games, survival horror regularly has female leads, as they accentuate the genre’s key themes: betrayal, victimhood, individual powerlessness. Within a broader context of Chinese literature, O’Sullivan also highlights how female characters form tools for processing events, especially surrounding national trauma, a practice that Detention uses through the character of Ray, whose actions reveal the ‘moral quagmire’ faced by those living under martial law (pp. 235–7). Conversely, other games undermine such possibilities. 1992’s Darklands focuses on medieval witches and witchcraft. As Watterson notes, witches provide an opportunity to present women as powerful, as well as monstrous. However, in this game, they are viewed through a narrow lens, as a result of the misuse (intentional or not) of a 15th century German source, the Malleus Maleficarium. Furthermore, the female witches ultimately become secondary in the story to male practitioners of Satanic worship. Throughout these games, it is notable that the use of female characters provokes responses different to male counterparts, and that – when successfully applied – they are not simply male characters made female.

Alongside the diverse range of games examined throughout this volume, several papers also represent a diversity of approaches. As already noted, the inclusion of the Zelda franchise in this volume expands what an archaeology game can be, and Smith Nicholls’ approach to the game similarly expands the range of methodological frameworks with which we can examine games. A key area of debate concerning the franchise is the gender identity of the game’s principal characters, Link, Zelda, and also Sheik. Smith Nicholls draws upon recent trends in gender archaeology – and the general hesitancy of scholars to identity gender non-conformity in the past (pp. 278–281) – as part of their examination, demonstrating the power of non-binary representations to ‘bypass the impossibility space of gender binary’ (p. 286) in moving away from reifying misogynistic gender stereotypes. In the RPG Mount and Blade, Mussies explores the possibilities provided by playing as an avatar of the historic figure Gisla, using the avatar “as a starting point for research into her, and as a simulation with which I can connect to this particular historical context” (p. 204). In so doing, Mussies is aided by the use of what she terms ‘autiethnography’, that is autistic autoethnography, with the resulting research journal forming a primary tool with which to create an analysis. Such a tool also reminds us that scholars are not only researching the game when they play it, they are also participants and capturing their own experience is an important part of the process. In her study of the ‘new’ Lara Croft (that is, the Lara of the 2013 reboot), Engelbrecht employs the framework of fourth wave feminism, revealing how reading Lara in this way contributes to our understanding of the character – one of the most famous fictional archaeologists in the world – including her desexualisation, relationships with men, and the role of her deceased mother. Such a reconfiguration of the character contributes to the much-needed rebranding of popular archaeology.

Aliyah Elesra in Heaven’s Vault. Inkle (2019). Image via PS4 share by J. Cromwell.

And this brings us to an issue that transcends video games. The representation of archaeology in games is not just a question of how the discipline is presented but of the wider societal influence that fictional figures have in the shaping of public understanding of the profession. Chief among such characters are Indiana Jones, Lara Croft, and more recently Nathan Drake, none of whom is confined to a single medium (note that, at the time of writing, a new Indiana Jones game is in the works by MachineGames). While identified (and identifying in-game) as archaeologists, these characters are rather looters, yet they have become synonymous with the discipline. As a brief personal analogy, as a student of Egyptology I was regularly asked if I wanted to be Indy or Lara (the answer was neither; at that point I hadn’t watched their films or played their games). They also form part of a particular branding of professional archaeologists; note, for example, the Twitter handle of archaeologist Dr Sarah Parcak (@indyfromspace), and the Instagram account of Dr Colleen Manassa (Vintage_Egyptologist), which in part echoes the general colonial-era aesthetic of Indiana Jones.4 As Draycott notes, it’s time for a re-brand, and alternatives are presented in three women: the ‘new’ Lara Croft, Chloe Frazer from Uncharted, and Aliyah Elesra in Heaven’s Vault. Engelbrecht’s treatment of the ‘new’ Lara has already been discussed, while the other two women – both women of colour – are less well-known. Arbuckle MacLeod examines the three main women in the Uncharted series, with particular focus on Chloe Frazer. Regarding her archaeological practice, there are subtle indications throughout of the specific difficulties faced by women in the field, and a stand-out episode in the game is her decision to leave artefacts with their rightful owners, rather than keep them for personal profit, simply because it’s the right thing to do. However, some important negative features of the archaeological trope still persist, namely the use of violence and damage to sites. Aliyah Elesra represents a different type of character, and one inspired by a real-life person, the Egyptian Egyptologist Dr Monica Hannah. Heaven’s Vault has no combat (although there is the threat of violence on multiple occasions, depending on which of the branching paths the player takes), and Aliyah is notable for her intelligence and reliance on multiple individuals who support her research, e.g., the museum’s archivist Huang. She’s also a disabled archaeologist, suffering from a fatal lung condition, although this is not made overt until the end of the game, as Draycott notes, creating a missed opportunity in terms of exploring this aspect of her character. However, while Draycott nods to the potential to play the game in an unsound archaeological manner, based on my own multiple play-throughs, it’s typically much easier to play as a looter and dealer than an archaeologist, keeping objects for your own benefit, even if that benefit is the pursuit of knowledge rather than financial gain. But, does taking such a route say more about the player or about the game?

In addition to exploring the historicity of games and the roles that women play, many contributions also remind us that games do not exist in a vacuum. They not only reflect other popular media and politics, but also the companies that make them. Several papers refer to the 2014 online harassment campaign, Gamergate, which directed vile attacks against women and a move towards diversity and progressivism in the video game industry. The #MeToo movement also revealed systemic misogyny in the industry, including within Ubisoft, who is discussed at multiple points in this volume because they are responsible for the Assassin’s Creed franchise. Santos’ paper in particular examines how controversies in development companies influence character creation, as well as what characters are used – or not used – to promote games (spoiler: male characters dominate). The opinion persists that female characters do not sell games, leading to modifications that provide alternatives to playing as a female, including most recently the lead character of Assassin’s Creed Valhalla, Eivor. Despite being canonically female, a male version (same name and storyline) was included to expand engagement from male players, and it was this version of the character that proceeded to dominate advertising for the game. In light of this broader context, the chapters in this volume all emphasise the need to promote other voices, not simply to justify the presence of women (and gender non-conforming individuals) in historical video games but to address a long-standing historiographic imbalance that also minimises their roles in history. This volume stands at the vanguard of this movement, soon to be followed by an edited volume by Jane Draycott and Kate Cook on Women in Classical Video Games, and represents an important contribution to scholarship on archaeogaming and historical gaming, as well as studies on gender in video games and women playing games.

These statistics are noted at several points throughout the volume.

On this point, i.e., what constitutes an archaeological game, see Andrew Reinhard, Archaeogaming: An Introduction to Archaeology in and of Video Games (Berghahn Books, 2018), and ‘Archaeology of Abandoned Human Settlements in No Man’s Sky: An Approach to Recording and Preserving User-Generated Content in Digital Games,’ Games and Culture 16/7 (2021), 855–884.

Kirk McKeand, ‘How well does Assassin’s Creed Origins capture history? We asked an Egyptologist,’ PCGamesN, 15 January 2018.

On this general trend, see Katherine Blouin, Monica Hannah, and Sarah E. Bond, ‘How Academics, Egyptologists, and Even Melania Trump Benefit from Colonialist Cosplay,’ Hyperallergic, 22 October, 2020.